“Real” marketing has always been a closed-loop system. Anyone who has spent time inside the function knows this instinctively. And they know more than just how to market, they know when not to. At its core, successful marketers understand people, shape value, and create the conditions for exchange. Executed properly, successful marketing is about making decisions, not about activities. Yet the lived reality of modern practice often feels disconnected from that purpose. We have an endless ability to reach people, paired with far less clarity about whether we should, or what earns the right to do so.

This tension has been building for decades, and is exacerbated every time access expands faster than discipline.

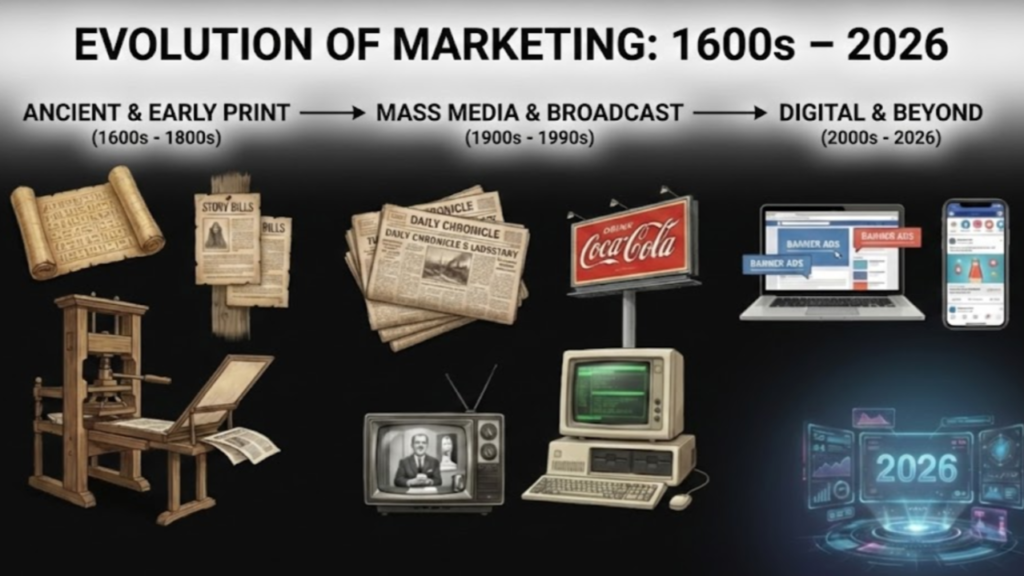

Early merchants operated with more intentionality than many teams today, in part because the environment demanded it. In Pompeii, producers stamped their names and quality claims onto amphorae , the ancient clay vessels used to transport goods (who knew?). Not for decoration but differentiation, a signal of trust in markets where choice existed, but abundance did not.

Mesopotamian traders used seals that functioned as both verification and branding, signaling credibility in relatively constrained competitive fields. Cylinder seals served as legal and commercial authentication in trade as early as 3000 BCE.

As media evolved, the system adapted without changing its core logic. Egyptian artisans used papyrus notices to extend their reach. Fifteenth-century handbills promoted specific offers following the spread of the printing press. Seventeenth-century newspapers organized listings so buyers could evaluate options side by side. Distinctive shop signs helped customers recognize merchants by symbol rather than literacy, a necessity in pre-modern retail environments.

Competition existed, but it was finite. Attention was scarce, but not yet saturated. Value had to be defined before it could be promoted. The operating principle was simple: clarity before contact.

Industrialization changed things. Mass production dramatically increased market sizes and forced companies to build more complex systems behind their products. By the early twentieth century, advertising volume exploded alongside national distribution. In the United States alone, aggregate advertising spend grew from roughly $200 million in 1880 to nearly $3 billion by 1920.

Companies like Procter & Gamble didn’t just run ads. They invested in product design, brand signaling, distribution, and sustained audience reach as a coordinated whole. Ivory Soap, introduced in 1879, became one of the first nationally branded consumer products, emphasizing purity and consistency as differentiation.

By the 1930s, P&G formalized brand management, assigning ownership and accountability at the product level, a structure that would later become standard across consumer goods. This was not creative experimentation. It was organizational discipline focused on the consumer (e.g. tailored to the target market), and scale demanded structure.

Even then, marketing was not about individual ads. It was about an aligned system supporting long-term value creation.

The real inflection point for modern marketing didn’t arrive with social media or AI. It arrived in the 1990s.

Email collapsed distribution costs and normalized direct digital outreach. Banner ads emerged with the commercialization of the web in 1994. Early search advertising and pay-per-click models tied spend directly to measurable response, beginning with platforms like GoTo.com in the late 1990s.

For the first time, access scaled faster than organizational judgment. Reach became easy, volume became measurable, and discipline lagged.

Many of the assumptions that still shape marketing today were set in that decade. That more activity meant more impact. That response equaled intent. That technology could substitute for strategy. The fundamental mission of marketing didn’t change, but it sure became easier to act without alignment, focusing on shiny martech and spraying and praying “content” all over the internet.

The 2000s and 2010s layered on real-time analytics, social platforms, automation, and programmatic buying. Tools improved. Visibility increased. But marketing fractured as teams optimized channels instead of customers. Metrics multiplied. Tech stacks ballooned.

The result is familiar to anyone working inside the function today:

Marketing didn’t lose its purpose. It exposed how fragile the system becomes when contact is easier than coherence.

Privacy restrictions, rising acquisition costs, and automation-driven execution are no longer abstract ideas. They define daily work. After years inside systems spanning email, SMS, paid media, and lifecycle programs, the shift is obvious. You cannot text whenever you want. Federal law limits outreach to specific hours under the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA). Carrier rules narrow that window further. You may reply if a customer initiates, but you cannot initiate freely. Consent governs timing, frequency, and whether a message is permitted at all.

These constraints are enforced through law and infrastructure, not preference. Carrier compliance programs now sit between brands and audiences, throttling or blocking messages before they are delivered.

Meta policy increasingly functions as regulation. In financial services, even language as basic as “open an account” or “visit us” can be prohibited in paid media due to platform enforcement of financial advertising policies (Meta Ads Financial Products Policy). Not because intent is unclear, but because outcome-oriented messaging carries downstream risk. Conversion language is denied. Educational framing is favored. The funnel is flattened upstream by design.

This is not a creative limitation. It is a systemic one. When platforms restrict not just targeting, but language itself, they are signaling that access without discipline is no longer acceptable at scale.

Email, retargeting, and identity-based advertising operate under similar pressure. Opt-outs must be honored immediately under CAN-SPAM. Purpose must match disclosure under GDPR and CPRA frameworks (EU GDPR, California CPRA). Access is conditional and revocable.

The assumption that more reach automatically creates more value no longer holds. At scale, access is not an advantage on its own. It is a responsibility, a cost center, and, when misused, a liability.

Organizations performing reliably today are asking a more fundamental question: If we can reach anyone, should we, and what earns that right?

When I talk about a “system,” I’m not referring to campaigns or tools. I mean a cohesive go-to-market system. Strategy, structure, people, process, and technology working together.

When these elements work together, marketing regains coherence. Contact becomes intentional. Signals regain meaning because the work reconnects to value.

Marketing’s history shows a consistent pattern. When the system is aligned, organizations create real value that markets reward. When the system fragments, access turns into noise and trust erodes.

We now have unprecedented power to reach people, and less certainty that doing so produces anything meaningful beyond irritation and unsubscribes.

The question governing the next era of marketing is simple. Will the discipline continue building mechanisms that interrupt because they can, or return to systems that earn attention because they should?

Companies rebuilding go-to-market around restraint, alignment, and judgment are already showing where the advantage lies. The rest are still sending messages and counting activities.